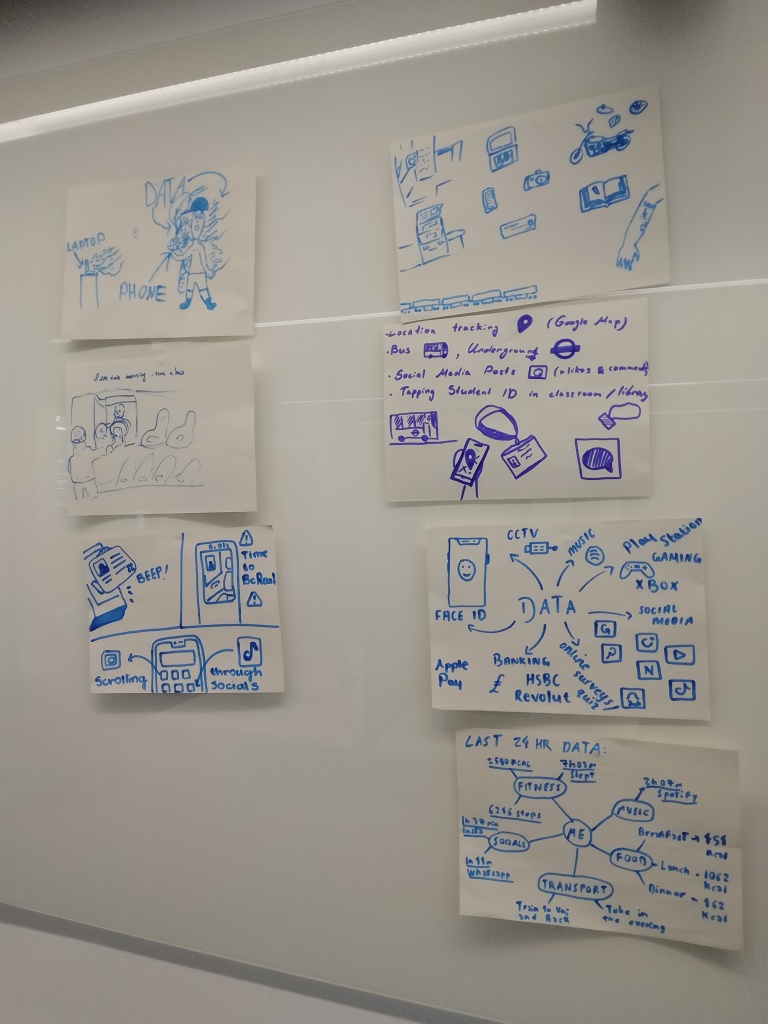

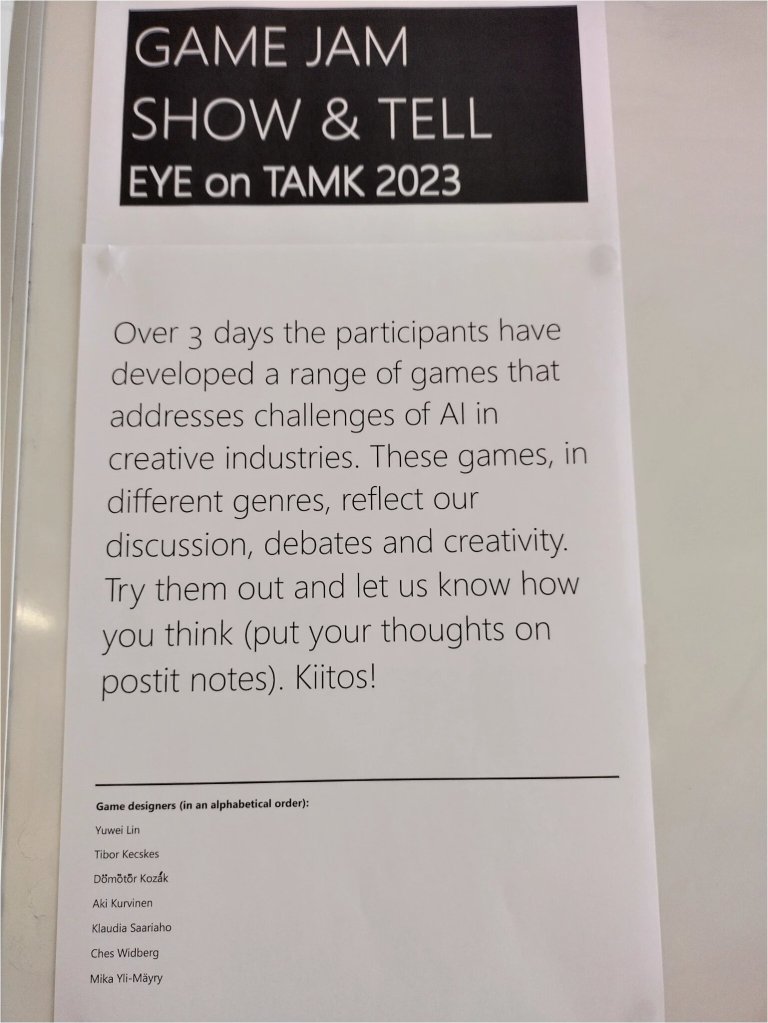

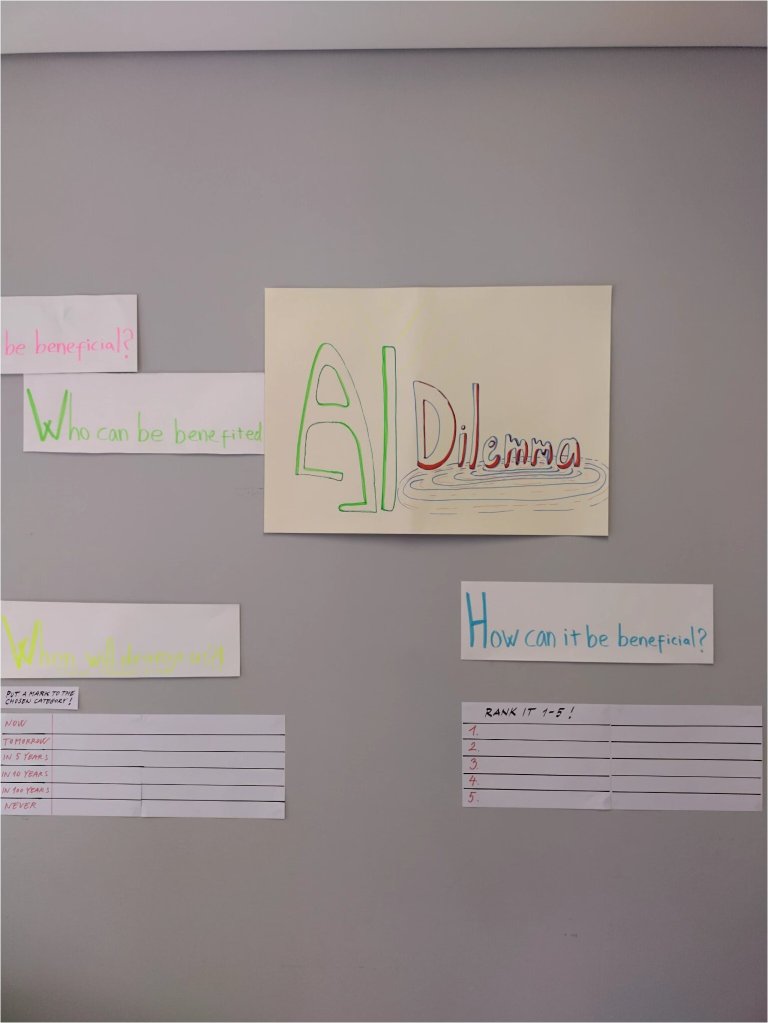

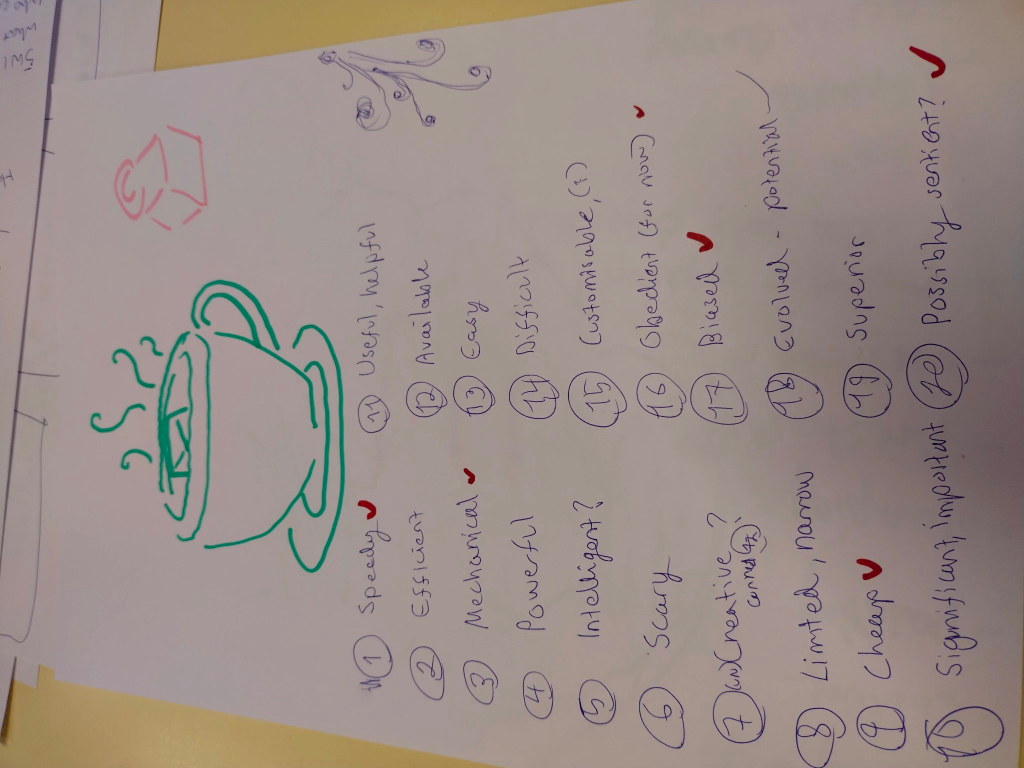

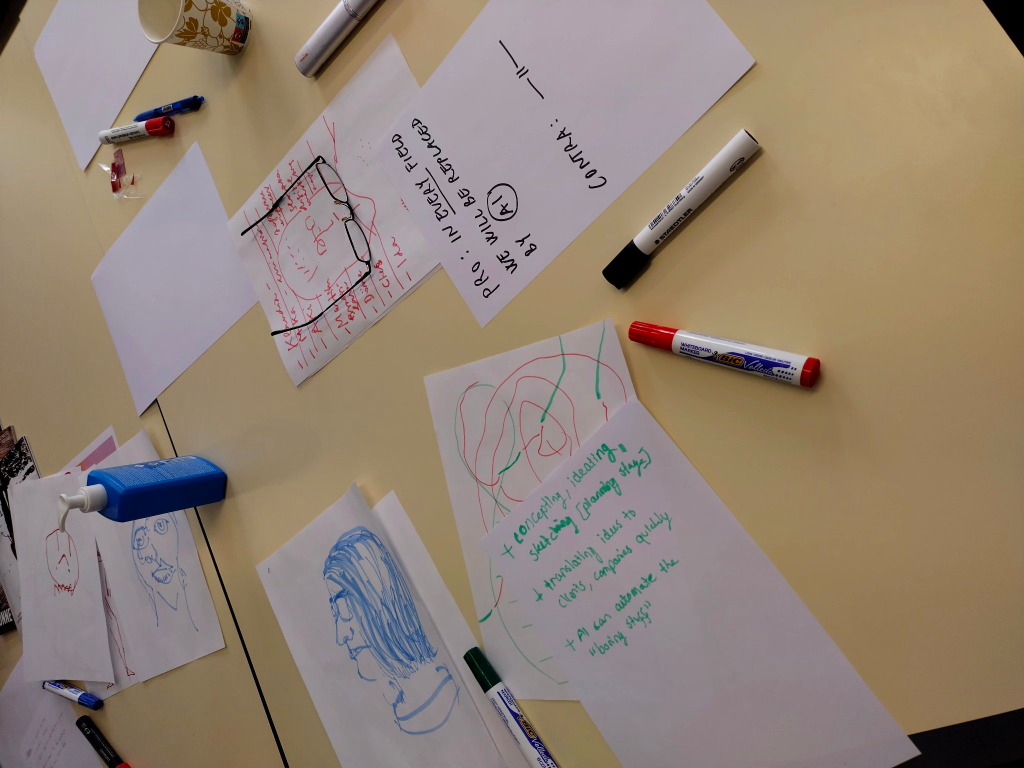

In the past months, I’ve partnered with Tactical Tech to trial a critical pedagogy – Critical Change Lab. It aims to develop critical literacy for young people in Europe. This pedagogical workshop model uses participatory, creative and critical approaches to encourage young people to think about their relationship to everyday technologies (e.g., social media platforms, apps, mobile phones) – in order to act on them. Through exploring the concepts of ‘influence’, ‘influencers’, ‘hidden influencers’, ‘persuasive design techniques’, we navigated the contemporary digital landscape critically and reflectively in a series of workshops. We asked ourselves some mundane questions: What has driven us to stay on YouTube longer? What has prompted us to spend more money on Amazon? What is recommending content to us on social media platforms such as TikTok?

During the trial period, two big news happened: The US House of Representatives has passed a divest-or-ban law that could lead to total TikTok ban. The European Commission opens proceedings against TikTok under the Digital Services Act (DSA) regarding the launch of TikTok Lite in France and Spain, and communicates its intention to suspend the reward programme in the EU. The former highlights the tension between freedom of speech and national security, whereas the latter reminds us of the lack of effective age verification mechanisms and the suspected addictive design of the social media platforms. These real-life episodes gave us much to discuss in the workshops.

Today (as of 8th May 2024), Ofcom has published their draft Children’s Safety Codes of Practice which require tech firms to have more robust age-checking measures, and to reformulate their algorithms to steer children away from what it called “toxic” material. There are more than 40 practical measures which regulates what online services should do to meet their legal responsibilities to protect children online. While it is a step towards full implementation of the enacted Online Safety Act 2023, many (parents of children who died after exposure to harmful online content, in particular) have described the proposed new rules as “insufficient”.

Indeed, I’d argue that we need greater transparency and more information to monitor the progress and changes made by tech firms in order to investigate what algorithms (persuasive design / addictive design techniques) have been implemented by these social media platforms and apps to enable and enhance their services (for advertising or other purposes). Tech firms should transparentise what algorithms they remove or configure and how. They need to do more than instrumentally inserting pop-up messages to warn under-18s about overuse of social media or harmful content, which can easily be ignored. The regulators have to steer tech firms to be more proactive and responsible in dealing with the socio-technical challenges.

Critical Change Lab or similar educational initiatives (please get in touch if you know any of such initiatives, no matter what scale they are at) are doing a tremendous job in addressing the socio-technical challenges from the bottom up. Only when humans retain our agency and autonomy, we will not be retired by algorithms / machines. I’d propose to ask tech firms to donate at least 1% of their global revenues to invest educational initiatives such as Critical Change Lab – it’s a fair ask and it’s for the long-term good of human race.