Data is everywhere, ubiquitous and plentiful. But data labour, which renders data, is often invisible, hidden, and unpaid. The rights of data workers are oppressed and overlooked. This is particularly true in the case of ‘fluid data’ (Shacklock 2016) in a marketised higher education sector.

Learning analytics, as defined in the first International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge in 2011 (LAK11), is ‘the measurement, collection, analysis and reporting of data about learners and their contexts, for purposes of understanding and optimising learning and the environments in which it occurs’.

Much has been said about the utilities of data in a data-centric higher education sector (see for example Shacklock 2016, Sclater et al. 2016, Palmer and Kim 2018). But in general, learning analytics means using aggregated information resulting from the analysis of the data gathered from class activities with the aim of improving instructional design, enriching didactic methods and better understanding the role of educational agents, developing frameworks for improving strategic decision-making, organizational design, and curricular policies. It can be understood as using educational data mining to analyse student behavioural patterns and to establish relationships between the variables involved in learning processes and learning outcomes.

Here at Roehampton University, for example, reading list analytics has been used as ‘an indicative measure of student engagement’ (Celada 2019). Librarians check student engagement with the lists using the Resource Lists analytic tool, and other tips to help enhance the student experience.

Moodle, Canvas, Blackboard, TurnItIn, FutureLearn MOOCs. All these virtual learning environments (VLEs), all offer what Greller and Drachsler (2012) describe ‘a powerful means to inform and support learners, teachers and their institutions in better understanding and predicting personal learning needs and performance’. However, data rights of the users of these VLEs and e-learning tools have rarely been discussed.

Admittedly, I have not discussed ‘data labour rights’ with my students when involving them in the class activities enhanced by some other cloud-based tools such as Nearpod and Kahoot.

Given the scandalous episode of Cambridge Analytica in 2018, and numerous breaches of user privacy and data rights, it is timely and important to consider ethical issues with learning analytics (Slade and Prinsloo 2013, Pardo and Siemens 2014).

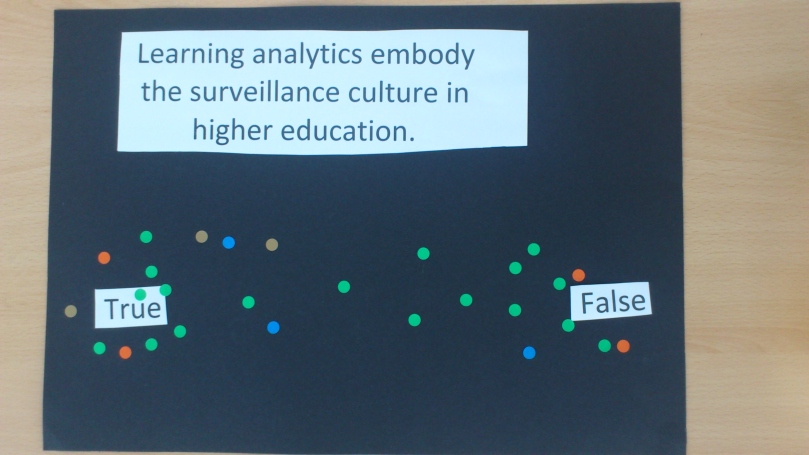

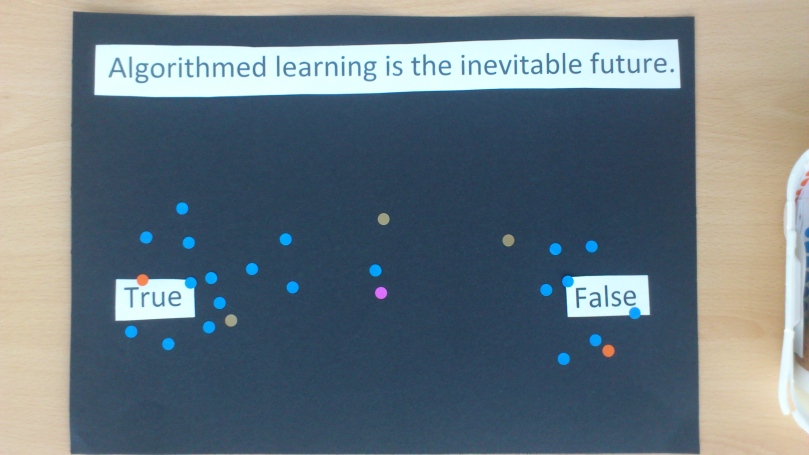

My first data art piece installed at Roehampton’s Learning and Teaching Festival (10-12 June 2019) surveyed opinions about learning analytics in the higher education sector. This ‘interactive poster’ exhibition, initially conceived to make up a late submission for an interactive seminar, also unexpectedly revealed the embodied process of labour of making learning analytics, and shows how nontrivial and nonlinear the process of data production is.

There were five A3 posters, each of which has a provocative statement printed on it. Delegates were invited to take the round dot stickers of different colours to express your views about these provocative statements on a True-False spectrum. Here are the outcomes:

These five diagrams offer some insight into what the delegates at #LandTFest2019 thought of ethical issues about learning analytics. The realisation of these diagrams also ‘documented’ a few issues about data labour and data quality.

Let me start by discussing the design and creation of the posters.

The outlook of the posters was an accidental success. It was difficult (and expensive) to print white characters on black papers. So I had to print out the statements, manually cut them with a scissor and them glue them on the black papers. But, the handmade craft feature surprisingly turned out to be good looking (well, the beauty of imperfection). It also signified the analogue texture of the digital matters in question.

The nonlinear datafication process

This self-selective respondents who opted themselves in to take part in this “survey” of this interactive art work also showed a nonlinear thought process. They did not just put a dot randomly on the posters; they read the statements, went through a rather long (more than 10 seconds) thought process, and then took the action of sticking a round dot on the black papers.

And, just like some vaguely designed questionnaires, they were pondering how to interprete the phrases such as ‘one-dimensional learning’, ‘inevitable future’, and ‘surveillance culture’.

One respondent said, academics have always take students ‘data rights’ very seriously. So this participant firmly put a dot on the ‘True’ end of the statement ‘Higher Education takes students’ data rights seriously.’

One respondent thought that not all surveillance is bad. We monitor students attendance and performance in order to identify problems early so as to respond to them promptly.

One respondent thought ‘algorithmed learning’ has existed for a long, long time, even before the word ‘algorithm’ was invented. (The Arabic source, al-Ḵwārizmī ‘the man of Ḵwārizm’ (now Khiva), was a name given to the 9th-century mathematician Abū Ja‘far Muhammad ibn Mūsa, author of widely translated works on algebra and arithmetic.). So it’s not ‘inevitable future’; it is an ongoing and still developing trend.

These interesting qualitative responses, individual thoughts behind the decision making, however, could not be fully captured and preserved when all these data inputs were aggregated into a collective dataset. Loosing all these embodied gesture and footprints is one of the problems with big data datasets, as argued in the paper I co-authored ‘Co-observing the weather, co-predicting the climate: human factors in building infrastructures for crowdsourced data‘.

Common data processing issues such as missing data and data type errors are also materialised in these five diagrams. My original intention was to colour code responses to these five statements (purely for aesthetics). However, some participants did not know of this colour coding rule. With all stickers out there to be grabbed, some used one colour throughout the game without switching to other colours designated for different statements.

Colour coding reveals these unintended ‘inputs’ in this crowdsourced dataset. This highlights the importance of supervision, moderation, interference, guidance and instructions during the datafication process to ensure the quality of the data (may it be data collected from those who opt-in to take part in a survey or the production of transaction data).

The participation of delegates at the Learning and Teaching Festival was key to this project. The analogue incarnation of the posters helps reveal the often invisible data collection activity and the digital labour (and emotional labour) involved. It shows that there are mixed feelings (and very divided feelings) about learning analytics in higher education. It also shows that datafication is not a straightforward process, as one would have expected.

We need to know more about the social and political life of learning analytics in order to make better judgements and more informed discussion about how to protect the data rights of our students (when gathering information generated by student activity in digital spaces) users data rights and data labour rights in data-driven education. In line with the effort of the Data Workers Union, we need to raise awareness of data labour rights in surveillance capitalism. The co-production of this interactive piece materialises our collective ability to see.